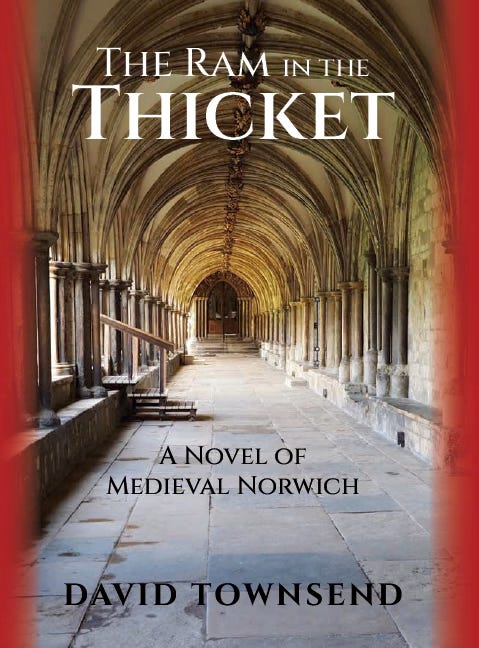

(Book cover adapted from Wikimedia Commons)

Just before Easter 1144, the body of a twelve-year-old boy turned up in Thorpe Wood, a little to the east over the River Wensum from Norwich.

Five years later, Thomas of Monmouth, a monk of the Cathedral Priory, wrote one of the most regrettable of all medieval literary survivals: an account of little St. William of Norwich's alleged murder at the hands of the Norwich Jews. It's the earliest full-blown narrative of the slander that Jews ritually murdered Christian children at Passover. Mercifully, Thomas's book only survives in a single manuscript. But it set such accusations loose in Europe, fomenting deadly levels of antisemitic bigotry, from the twelfth century up into modern times.

Thomas wrote the life of William in seven parts. He wrote only the first in 1149, when he must have seized on malicious rumours about the murder that had circulated orally in the city in the intervening years. His work blends mawkish, sentimental description of the child's piety and innocence with an account of the cold-blooded sadism of his captor-murderers. The description of the "martyrdom" could fairly be described as medieval splatter porn. In 1154 he wrote the next five sections, largely as a response to those who remained skeptical of claims for William's sanctity. Thomas couldn't let go of his obsession: he wrote a final seventh section of the work in 1172-3. He chronicles his own struggle to promote the boy's veneration at the Cathedral, and records a series of purported miracles worked by the child saint.

Sometimes antisemitism is talked about as though it floats free of specific historical contexts. But the cult of William tapped into other, more concrete resentments--resentments that Thomas played on, displacing them onto a vulnerable minority within the city.

The destruction of much of Anglo-Saxon Norwich at the hands of the Norman newcomers lay within living memory. People could still recall streets, houses, and churches demolished to build the new Cathedral and the Castle that loomed over the transformed city. Thomas claims that the Norman authorities protected his murderers. Most Jews lived the other side of the Castle from the earlier English town, in the New Burgh that the Normans had established, (The Jewish merchant Isaac Jurnet's house, which I mentioned a few weeks ago on our tour of St. Julian's Church, was an exception.) In the face of mob violence, local Jews would indeed have appealed to the magistrates for protection.

The story of William was a displacement for another story: that of English loss and indignity at the hands of Norman superiors. Thomas diverted resentment toward the city's masters onto an easy target, much as resentment of present-day economic dislocation is easily diverted from the corporate forces that cause it, toward vulnerable immigrant groups. Twenty-first-century bigotry isn't necessarily all that different from its medieval predecessors.

But the cult of St. Wiliam long survived the circumstances of its origin--and even the disappearance of the Jewish community with their eventual banishment from England in 1290. Once hatred is loose in the world, it has a life of its own. The stories of other "blood libel" saints proliferated, notably that of another child "martyr," Little St. Hugh of Lincoln--who is most definitely not to be confused with St. Hugh, Bishop of Lincoln, who stopped riots against the Jews in the late twelfth century. The tale told by the Prioress in Chaucer's Canterbury Tales is perhaps the best-known example in English literature.

William remained a fixture of Norwich Cathedral's life, with an altar dedicated to him in one of the side chapels, all the way to the English Reformation in the sixteenth century. The surviving records of the Sacristan's office include notations of the amounts offered in his honour year by year.

But the record of donations for the year 1413 is missing....

Thanks, David. Forwarded to Jewish friends.

This is brilliant as always, David. You have a wizard’s command of medieval history (of course! obviously!) but also a wicked wit (medieval splatter porn!). Such a delicious feast you spread before your readers.